Brief history of Intrum: The road to a cohesive credit management group

Today, Intrum works across Europe. The name comes from a small Swedish debt collection agency that was founded in 1923. From there, it grew through partnerships and mergers to become the market’s leading credit management firm – with roots that now go even further back.

In the 1920s, consumers across Europe and the US especially started buying more on credit, instead of paying cash up front. It was a time when the financial markets developed, driven by industrialisation and urbanization. Credit was then normally based on long payment terms, which meant consumers could easily accumulate more debt than they could pay off. This left business owners without payment. The built-in risk of credit purchases posed new challenges for businesses to secure liquidity and determine who was worthy of credit.

Stockbroker Sven Göransson saw a business opportunity in this. What if there was a business that helped other businesses secure cash flows? If that business was just profitable in itself, it would be a win-win. In 1923 he brought the first iteration of his vision to life, founding Justitias Upplysningsbyrå AB in the city of Jönköping. It had two parallel offerings: collection operations and providing credit information.

Pioneering debt collection

To help determine someone’s credit worthiness, Göransson got creative and built networks of local police officers that could help inquire about the finances of a business. He also brought a gentler approach to collection operations. Instead of sending bailiffs in special clothing to knock on doors, as was done in other parts of Europe, Justitia began each collection process with a letter before moving on to other, also non-confrontational measures.

Over time, this would help in reversing the negative perceptions of debt collectors.

Similar debt collection and credit in formation operations appeared in other parts of Europe. In Norway, a family-run collection agency called Creditreform was already established in 1898. This company, under the name of Lindorff, would become an inseparable part of Justitia’s history many years later.

Company split for a fresh start

Justitia’s greatest competitor in the credit information sector during this time was Soliditet. As Göransson saw greater potential in debt collection, he sold off the credit information side to Soliditet. Göransson focused on specialised debt collection under a new name – Justitias Inkasso och Juridiska Byrå AB.

Sven sold half of the business to his main competitor. Hald a century later, his son Bo bought it back.

He got a good price by agreeing to never engage in credit information again for the rest of his life. Soliditet forgot to include his offspring in that setup though. Fast forward to 1973 and a law was enacted that prohibited foreign ownership of Swedish credit information businesses. By then, Soliditet was owned by foreign owners. As a result, Justitia, which now had Sven’s son Bo at the helm, was happy to buy out one of his father’s greatest antagonists from its foreign owners.

Becoming the Swedish market leader

Justitia’s fresh start in the late 1930s was quickly overshadowed by the outbreak of World War Two. It would take until the postwar period for more favourable economic conditions, and a surge in purchases on credit, before the business took off again. This was the time that Göransson started building a position as a national market leader. By the 1970s, Justitia held a clearly dominant position in Sweden.

“During this period, we bought virtually everything that existed. I collected a lot of stamps in my passportBo Göransson, Longtime CEO of Justitia

After helming the business for almost 50 years, Sven Göransson in 1970 sold the business to his son, Bo. The company that Bo took over had 30 employees, and could almost be said to be struggling: its margins were thin and revenues were declining.

Bo adopted a more aggressive expansion policy, based primarily on acquisitions of Swedish competitors. He also wasted no time in going abroad. In 1971, a Swiss entrepreneur wanted to use the name Justitia, and contacted Göransson. Bo saw a winwin opportunity and suggested they go into business together. After that first venture outside Sweden, many more followed.

A new service

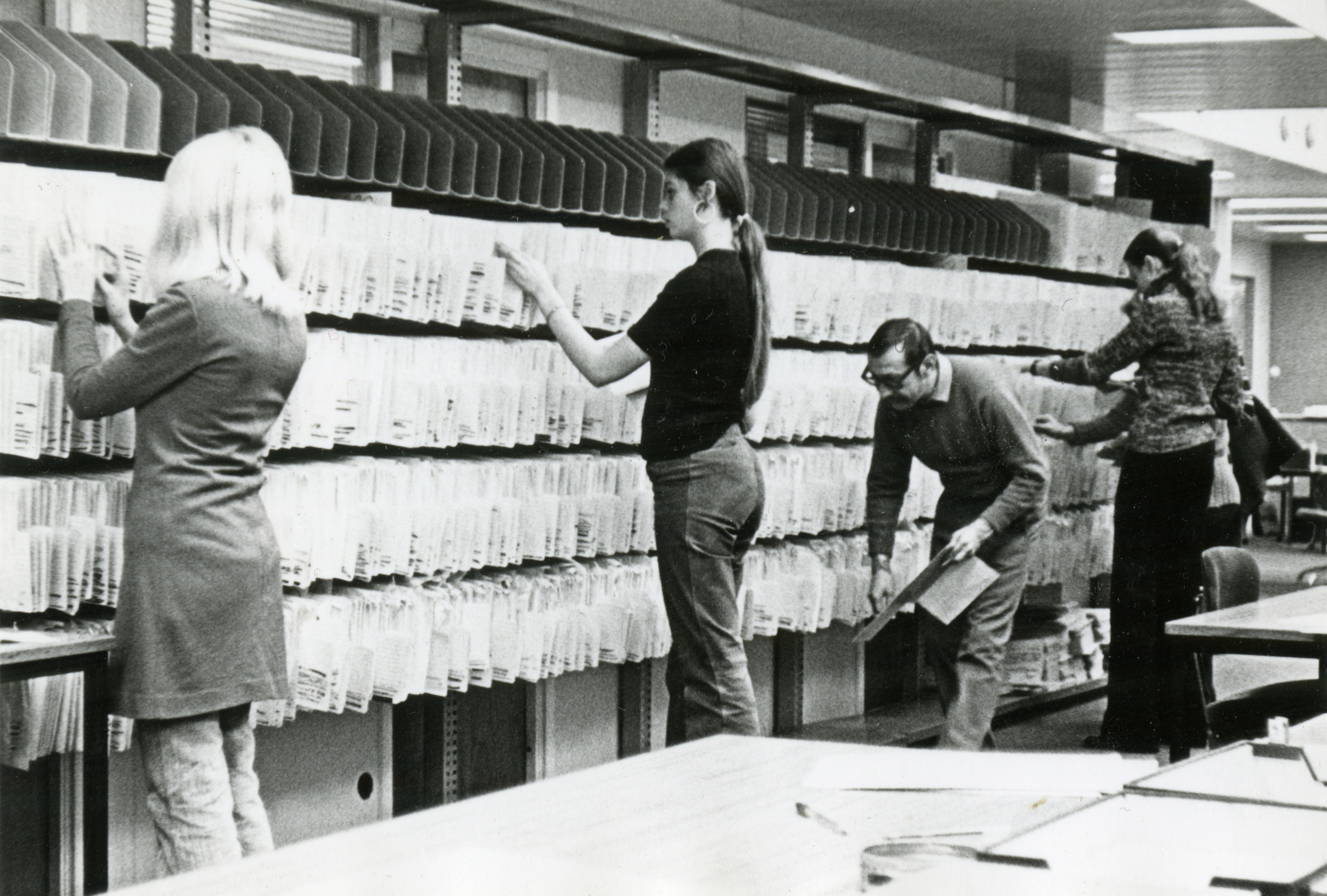

During the 1970s, the group innovated a new service: managing accounts receivable for companies. (“Accounts receivable” being the term for any amount of money owed by customers, but not yet paid, to a company.) The idea came from an employee at Justitia who saw heaps of receivables at a local television shop. He was amazed at how many customers must owe that company money. The customers were not necessarily behind with their payments, but they still represented a liability to the company. Göransson and his team saw an opportunity. They started storing accounts receivables files for corporate customers across Sweden, sharing the amounts that could be collected 50–50. This spread to other markets and the group became a Nordic leader in accounts receivable management.

A brand new name: Intrum Justitia

By 1982, Justitia had expanded to Finland, Norway, Denmark, and Ger many. However, in each market, the companies worked under different names. Göransson wanted a shared name – and took inspiration from a crime novel that he had read. In it, he found a name he liked and so he changed the corporate name to Intrum Justitia, for all Group companies.

Expansion continued in the mid1980s to include the Netherlands, Italy, France, and Belgium. In the early 1990s, Göransson acquired UK based CAS Group PLC, establishing Intrum as the B2B market leader in one of Europe’s largest financial hubs.

Following the collapse of the Iron Curtain, Intrum expanded during the 1990s into Eastern European markets. By 2003, the Intrum Justitia Group was present in 21 countries with SEK 2.7 billion in revenue and a profit of approximately SEK 240 million.

Getting the word out

In the 1990s, Intrum started to actively engage in branding ventures. The goal was to both get the company name out and to tackle negative perceptions of debt collection companies head on.

The Group’s initiatives included:

- Ocean race sponsorship: Intrum sponsored a multinational crew in the 1993–1994 sailing race Whitbread Round the World. The ship called at several European ports and came in second place overall in the main race. The ocean race was followed by 750 million people around the world.

- “Fair pay please”: In the 1990s, Intrum ran promotional campaigns playing on football association FIFA’s ”Fair play please” slogan.

- “Spending responsibly”: Intrum’s spending responsibly campaigns were innovated in Switzerland and also ran in the Nordics. At their height, the President of the Swiss Confederation awarded a prize to hundreds of students who wrote essays on this topic, sponsored by Intrum in 2006–2010.

By the early 2000s, Intrum was active across Europe, but each country was run in isolation from the others. CEOs Michael Wolf (2006–2008) and Lars Wollung (2008–2016) worked to bring the various parts closer together as one group. Wollung in particular worked to replace competition with collaboration, calling it “The Intrum Way”.

With digitalisation, more staff could work in centralised head offices instead of regional teams. This change process of alignment and harmonisation led to a reduction in the number of regions from 7 to 3 and far fewer branch offices within a given country.

The employees are the lifeblood of Intrum. Their performance and dedication cannot be bought, but has to be earnedThomas Hutter, Managing Director of Intrum Switzerland

A new service for banks

During the late 1990s, Intrum saw a new growth opportunity, built on digital data analysis and a need from the banking sector: portfolio investments (PI). These were nonperforming loans (NPLs) that banks and financial institutions sold to a third party, such as Intrum.

By 2010, Intrum was offering PI services in most of its markets and that business was almost matching the debt collection operations in revenue contribution and significance.

Two credit giants merge

Norway’s Creditreform, founded in 1898 had by the 2010s also grown into a Europewide company, now called Lindorff. These two leading European debt collection groups, both based out of the Nordics, were in heavy competition in several markets. But then, in 2017, they decided to join forces instead.

The merger was on such a scale that European competition authorities had to approve. As a result, overlapping markets were divested, which was a major change but also a chance to create an efficient organisation.

The merger did shake the organisations, though. Anette Willumsen, today senior advisor at Intrum, was managing director of Lindorff Norway at the time: “When I announced at Lindorff that we’d merge with Intrum Justitia, emotions ran high. There were tears from longtime employees at the thought of merging with their arch-rival. I can see that it has paid off, though. Old animosities have subsided, everyone is working together as a team, and we have already achieved greater success together then we ever could have apart.”

Both Intrum Justitia and Lindorff took pride in having open corporate cultures, which probably helped rally the employees around the change journey that the merger required.

They shared many other historical similarities, too.

Historical parallels

Eynar Lindorff was Creditreform’s first CEO. Just like Göransson’s Justitia in Sweden, Creditreform had both credit information and debt collection operations. Inspired by a business model from Germany, it also charged memberships fees for its services.

In 1911, the company was sold to Leif Juel Moltke Hansen and his business partner Harald Schjoidager. Leif ’s son Otto eventually succeeded him.

Father and son Moltke Hansen ran Creditreform as CEOs for a combined 76 years from 1911 to 1986, not dissimilar from how father and son Göransson ran Justitia for little over 70 years from 1923.

Like Intrum Justitia in Sweden, Creditreform grew strong in its home market before expanding internatio nally through mergers. By 1998 Credit reform had about 350 employees, followed shortly by a name change to Lindorff, after its first CEO.

Synergies in secured assets

After the merger in 2017, the joint company was now called Intrum.

Expansion into new segments continued. One such area was secured assets, loans secured by collateral such as property. But unlike portfolio investments, when banks sell debt to Intrum, the secured assets business was built upon Intrum taking over full collections departments, including both employees and nonperforming loans (NPLs).

Soon enough, huge such “carveout” acquisitions were made in Italy and Greece. The first came from Italian Intesa Sanpaolo in 2018, followed by Greek Piraeus Bank in 2019. These deals drove astronomical growth in the secured assets business that the Group is still building on as it celebrates its centennial in 2023.

Culture of reflection

Of course, continued growth over 100 years (and in Lindorff’s case over 125 years) wouldn’t have been possible without a corporate culture that encourages everyone to constantly reflect on how it operates.

Which services and products should be offered? Which types of skills are required to offer that? How should everyone work together?

These are questions that every passing generation at the Group has had to answer, no matter what their organisation looked like at the time. Today’s Intrum Group is continuing to build on that heritage, as it helps companies prosper by caring for their customers – and while continuing to fulfil the company vision of being trusted and respected by everyone who provides and receives credit.